Sustainable water resource management has emerged as one of the most pressing legal and governance challenges of the twenty-first century. Accelerating climate change, population growth, urbanization, and competing agricultural, industrial, and ecological demands have placed unprecedented stress on finite freshwater resources.

By 2026, water scarcity will no longer be a projected risk but a lived reality across multiple regions, from transboundary river basins in South Asia and Africa to groundwater-dependent economies in the Middle East and North America. Making effective legal frameworks is therefore essential for equitable allocation and long-term sustainability, as according to UN-Water:

“By 2025, half of the world’s population will be living in water-stressed areas.”

International institutions increasingly recognize that water governance is inseparable from human rights law, environmental protection, climate adaptation, and international economic regulation. UN-Water estimates that nearly half of the world’s population now lives in water-stressed areas, transforming water from a sectoral issue into a core concern of international law and global security. Effective legal frameworks for Natural Resource Management are therefore essential not only for equitable allocation but also for conflict prevention, ecosystem protection, and sustainable development.

This comprehensive guide examines water management laws, integrated water resources management (IWRM) frameworks, groundwater and surface-water regulation, water allocation systems, and environmental compliance requirements governing sustainable water use in 2026, while situating these regimes within ongoing legal and institutional change.

Foundations of Global Water Law

Global water law does not operate through a single comprehensive treaty. Instead, it consists of overlapping principles derived from international treaties, customary international law, regional agreements, and judicial decisions.

At its core are the principles of equitable and reasonable utilization, the obligation not to cause significant harm, prior notification and consultation, and cooperation among riparian states. These principles are reflected in the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses and have been reinforced through state practice and international adjudication.

International human rights law has further reshaped water governance. The recognition of access to safe drinking water and sanitation as a human right imposes positive obligations on states to ensure availability, quality, affordability, and accessibility. In 2026, courts and treaty bodies increasingly interpret water management failures as potential violations of the right to life, health, and dignity.

Environmental law adds another layer, requiring states to protect aquatic ecosystems, maintain environmental flows, and prevent irreversible ecological harm. Climate law now intersects directly with water law, as states must adapt allocation systems to hydrological variability driven by global warming.

Transboundary Watercourses and International Obligations

Transboundary rivers, lakes, and aquifers supply water to hundreds of millions of people, making international cooperation a legal necessity. Global water law requires states sharing watercourses to manage them cooperatively and sustainably.

The principle of equitable and reasonable utilization does not mandate equal shares but requires consideration of factors such as population dependence, existing uses, climatic conditions, and ecosystem needs. In practice, this principle has become central to resolving disputes in basins such as the Nile, Indus, Mekong, and Euphrates-Tigris systems.

The obligation not to cause significant harm limits unilateral development that would materially damage downstream states. While not an absolute prohibition, it requires mitigation, consultation, and compensation where harm occurs. International courts have emphasized that environmental damage and water deprivation can constitute legally cognizable harm even in the absence of armed conflict.

Prior notification and information-sharing obligations ensure transparency for planned measures such as dams, diversions, or large-scale irrigation schemes. Failure to comply increasingly attracts diplomatic protests and legal challenges before international forums.

Integrated Water Resources Management as a Global Norm

Integrated Water Resources Management has evolved from a policy concept into a normative framework influencing legal interpretation at both domestic and international levels. IWRM emphasizes basin-scale planning, integration of surface water and groundwater, stakeholder participation, economic valuation, and environmental sustainability.

Global institutions promote IWRM as essential for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6, which commits states to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. In 2026, donor funding, development bank lending, and climate finance increasingly require alignment with IWRM principles.

Watershed-based governance is now widely recognized as legally preferable to fragmented sectoral regulation. International river basin organizations play a growing role in coordinating planning, data-sharing, and dispute prevention, although their authority varies widely.

IWRM Principles and Framework

Global Water Partnership defines IWRM as:

“a process which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources to maximise economic and social welfare equitably without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems.”

Core IWRM Elements:

- Basin-scale management recognizing hydrologic boundaries

- Stakeholder participation in decision-making

- Integration of surface water and groundwater

- Economic valuation of water resources

- Environmental flow requirements

- Climate change adaptation

- Demand management alongside supply development

Watershed-Based Planning

Effective water management requires watershed approaches addressing:

- Water quality and quantity interdependencies

- Upstream-downstream relationships

- Point and nonpoint source pollution

- Flood control and drought mitigation

- Habitat conservation for aquatic species

- Recreation and aesthetic values

Multi-Stakeholder Governance

IWRM emphasizes inclusive governance involving:

- Federal and state agencies

- Local water districts and utilities

- Agricultural water users

- Industrial facilities

- Environmental organizations

- Indigenous tribes

- Recreational interests

Groundwater and Transboundary Aquifers

Groundwater represents the world’s largest source of accessible freshwater, yet remains among the least regulated under international law. Over extraction, pollution, and climate-driven recharge variability have elevated groundwater governance to a critical legal issue. Groundwater supplies approximately 40% of U.S. public water systems and 50% of domestic water, requiring comprehensive management addressing overexploitation and contamination.

Groundwater Overdraft Challenges

Many aquifers face unsustainable extraction rates exceeding natural recharge:

- Declining water tables requiring deeper wells

- Increased pumping costs

- Land subsidence and infrastructure damage

- Saltwater intrusion in coastal areas

- Reduced baseflow to streams

- Ecosystem degradation

State Groundwater Regulation

States employ various regulatory approaches to groundwater management. Absolute ownership grants landowners unlimited rights to groundwater beneath property, though this approach has limited application today. Reasonable use requires that extraction be reasonable relative to aquifer capacity and other users’ rights. Correlative rights ensure that all overlying landowners share aquifer capacity proportionally during shortages.

Prior appropriation applies to groundwater in some western states using permit systems with priority dates. Most states now require permit systems for new wells above specified capacity, establishing allowable withdrawal rates, measurement and reporting requirements, well spacing and construction standards, and critical area designations with enhanced restrictions.

Conjunctive Management

Progressive management integrates surface and groundwater recognizing their hydraulic connection:

- Groundwater banking during wet years

- Strategic aquifer recharge

- Coordinated surface-groundwater allocation

- Protection of groundwater-dependent ecosystems

- Stream depletion analysis for new wells

The UN Draft Articles on the Law of Transboundary Aquifers articulate principles of cooperation, equitable utilization, and sustainability, signaling emerging customary norms. States increasingly recognize that uncontrolled pumping can violate international obligations where transboundary impacts occur.

At the domestic level, permit systems, abstraction limits, and monitoring requirements are expanding. Conjunctive management, coordinating groundwater and surface water use, has become a best practice in regions facing chronic scarcity.

Surface Water Allocation Laws

Surface water allocation systems determine who can use water, how much, for what purposes, and under what conditions.

Appropriation Permit Systems

Western states issue water rights through administrative processes:

Application Requirements:

- Proposed diversion location and quantity

- Beneficial use type (agriculture, municipal, industrial)

- Project description and timeline

- Environmental impact assessment

- Demonstration of water availability

Permit Conditions:

- Maximum diversion rate and annual volume

- Points of diversion and use locations

- Priority date establishing seniority

- Beneficial use requirements

- Return flow obligations

- Measurement and reporting duties

Water Rights Transfers and Marketing

Water marketing allows flexible reallocation responding to changing needs:

- Permanent transfers selling rights to new owners

- Temporary leases during drought

- Changes in use type or location

- State review ensuring no injury to other rights holders

- Third-party impacts consideration

- Public interest review

Instream Flow Protection

Recognizing environmental water needs, states establish instream flow protections through:

- Reserved water rights for fish and wildlife

- Minimum flow requirements below dams

- Acquisition of water rights for environmental purposes

- Bypass flows around diversions

- Seasonal flow variability maintaining natural patterns

Drought Management

States prepare drought contingency plans including:

- Monitoring triggers defining drought stages

- Progressive water use restrictions

- Priority system implementation favoring senior rights

- Temporary transfer facilitation

- Emergency well permits

- Economic assistance programs

Water Quality and Pollution Control Obligations

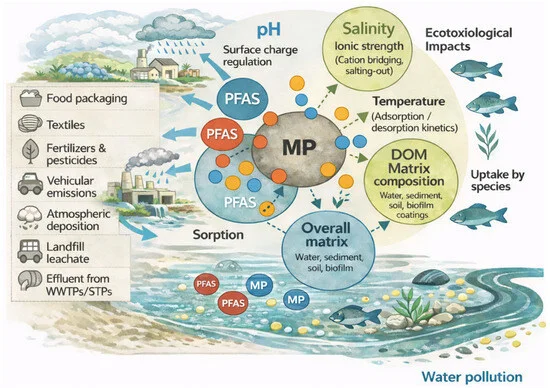

Global water law imposes obligations to protect water quality for human consumption, agriculture, and ecosystem health. International environmental treaties address pollution through frameworks governing hazardous substances, persistent organic pollutants, and marine pollution. The emergence of contaminants such as PFAS, pharmaceuticals, and microplastics has exposed gaps in existing regimes. In 2026, international cooperation increasingly focuses on monitoring, data exchange, and technology transfer to address these risks.

States are expected to adopt precautionary approaches, particularly where pollution threatens drinking water supplies or transboundary ecosystems. Failure to regulate industrial and agricultural runoff increasingly raises human rights concerns. Ensuring water quality for designated uses requires comprehensive standards and regulatory oversight.

Clean Water Act Standards

States establish water quality standards for all surface waters specifying:

Designated Uses: Swimming, fishing, drinking water supply, agricultural irrigation, industrial use, aquatic life support

Criteria: Numeric limits or narrative statements for pollutants protecting designated uses

Anti-degradation Policy: Three-tier system maintaining existing high-quality waters

Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs)

For impaired waters not meeting standards, states develop TMDLs calculating:

- Maximum pollutant amounts water body can receive while meeting standards

- Allocation among point sources (NPDES permits)

- Allocation to nonpoint sources (agricultural runoff, urban stormwater)

- Implementation plans achieving necessary reductions

Groundwater Quality Protection

States protect groundwater quality through:

- Classification systems based on use potential

- Numeric standards for contaminants

- Source water protection zones around public wells

- Underground injection control preventing contamination

- Agricultural best management practices

- Monitoring networks detecting emerging problems

Compliance Monitoring

Water users must demonstrate compliance through:

- Flow measurement at diversion points

- Water quality sampling and analysis

- Annual use reporting to agencies

- Record keeping and documentation

- Audits and inspections

Environmental Protection and Biodiversity

Aquatic ecosystems are now recognized as integral components of water governance rather than collateral concerns. Environmental flow requirements, habitat conservation, and ecosystem restoration have entered legal discourse at international and regional levels.

Treaties on biodiversity and wetlands impose obligations to protect rivers, lakes, and aquifers as ecological systems. Courts have increasingly linked ecosystem degradation to violations of environmental and human rights obligations. Water users face comprehensive environmental requirements protecting aquatic ecosystems and public resources.

Endangered Species Act Compliance

Water projects must avoid jeopardy to listed species and adverse modification of critical habitat:

- Section 7 consultation for federal actions

- Biological assessments analyzing project effects

- Reasonable and prudent alternatives minimizing impacts

- Habitat Conservation Plans for non-federal projects

- Flow releases supporting endangered fish

- Screening structures preventing entrainment

National Environmental Policy Act

Major federal water projects require NEPA compliance:

- Environmental Impact Statements for significant impacts

- Analysis of alternatives including no-action

- Public participation and comment periods

- Consideration of cumulative effects

- Mitigation measures minimizing harm

State Environmental Review

Many states have parallel environmental review laws requiring analysis of water project impacts on:

- Water quality and aquatic habitat

- Riparian vegetation and wildlife

- Recreational opportunities

- Scenic and aesthetic values

- Climate change implications

Dam Safety and Removal

Dam safety and removal have gained prominence as aging infrastructure poses risks to downstream communities and ecosystems. International development standards now require comprehensive environmental and social safeguards for water infrastructure projects. Aging dam infrastructure requires attention to:

- Regular safety inspections

- Emergency action plans

- Structural modifications meeting current standards

- Fish passage requirements

- Consideration of dam removal for ecosystem restoration

Climate Change and Adaptive Water Governance

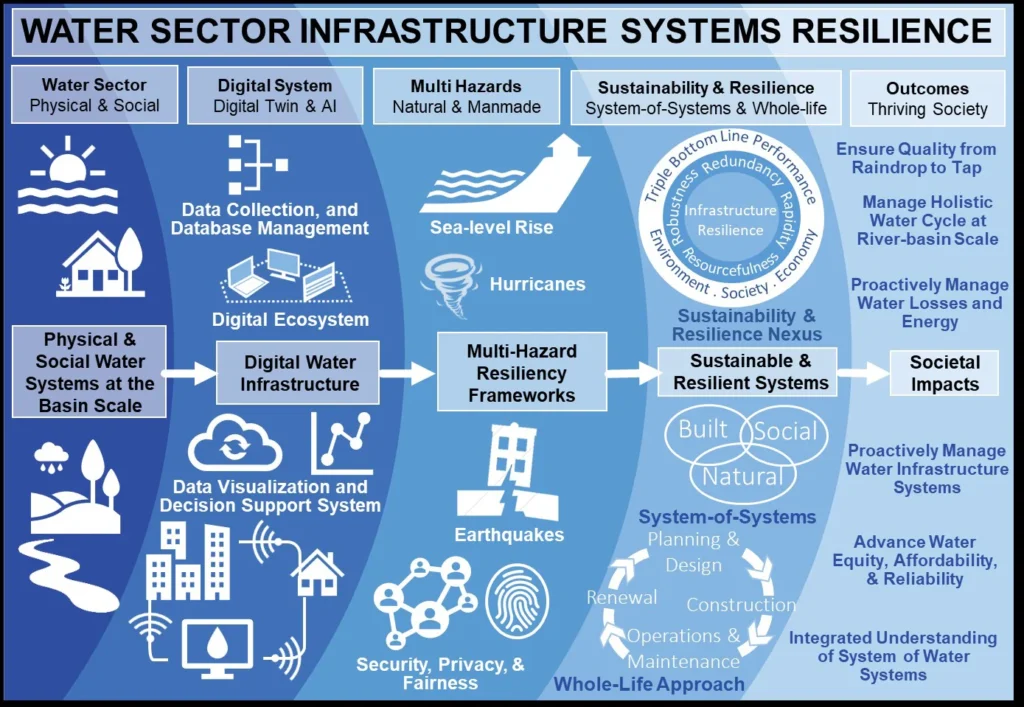

Climate change has fundamentally altered the assumptions underlying water allocation law. Reduced snowpack, altered precipitation patterns, intensified droughts, and sea-level rise challenge static allocation regimes. Global water law increasingly emphasizes adaptive management, flexibility, and resilience. Climate finance mechanisms support water conservation, storage, ecosystem restoration, and early-warning systems.

Legal frameworks now incorporate dynamic permitting, drought contingency planning, and conflict-resolution mechanisms designed to respond to uncertainty rather than historical averages. Climate change fundamentally alters water availability and management requirements necessitating adaptive strategies.

Climate Impacts on Water Resources

Water managers face:

- Reduced snowpack and earlier spring runoff

- Increased evapotranspiration

- More frequent and severe droughts

- Intensified flood events

- Saltwater intrusion from sea level rise

- Changed precipitation patterns

Adaptation Strategies

Effective responses include:

- Enhanced storage through reservoir expansion and groundwater banking

- Water conservation and efficiency programs

- Diversified supply portfolios

- Improved forecasting and operational flexibility

- Infrastructure hardening against extreme events

- Ecosystem restoration enhancing natural resilience

Legal and Institutional Adaptations

Climate adaptation requires:

- Updated hydrology in water planning

- Flexible permit conditions

- Coordinated regional management

- Increased monitoring and data sharing

- Conflict resolution mechanisms

- Adaptive management frameworks

Comparative and Regional Perspectives

Global water law operates across diverse legal, political, and hydrological contexts. While core international principles, equitable and reasonable utilization, the obligation not to cause significant harm, cooperation, and sustainability, are widely recognized, their implementation varies substantially across regions.

Comparative analysis reveals how legal traditions, institutional capacity, economic development, and geopolitical dynamics shape water governance outcomes. Understanding these regional approaches is essential to assessing both the strengths and limitations of global water law as it functions in practice.

South Asia: Treaty-Based Allocation and Judicialized Dispute Resolution

South Asia presents one of the most legally dense yet politically sensitive water governance environments in the world. The region relies heavily on bilateral treaties to manage transboundary rivers originating in the Himalayas, particularly between India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan. These agreements often focus on allocation and infrastructure development rather than ecosystem protection.

The Indus Waters Treaty stands as the most prominent example, establishing a detailed allocation regime and dispute resolution mechanisms involving neutral experts and international arbitration. Despite geopolitical hostility, the treaty has endured for decades, demonstrating the stabilizing potential of legally binding water agreements. However, critics note that the treaty reflects mid-twentieth-century assumptions, offering limited flexibility to address climate change, groundwater depletion, or environmental flows.

In Bangladesh and eastern India, water governance challenges arise from upstream diversions and flood control structures affecting downstream ecosystems and livelihoods. Legal mechanisms exist, but enforcement often relies on diplomatic engagement rather than adjudication. Regional courts have increasingly recognized water as a constitutional and human rights issue, signaling a gradual shift toward rights-based water governance.

Southeast Asia: Cooperative Basin Governance with Limited Enforcement

Southeast Asia’s approach to water governance emphasizes cooperation over adjudication. The Mekong River Basin illustrates this model, with the Mekong River Commission facilitating data sharing, joint studies, and consultation on major projects. The legal framework prioritizes consensus and political dialogue rather than binding enforcement.

While this approach has promoted regional stability, it has also exposed weaknesses. Large-scale hydropower development has proceeded despite downstream concerns, highlighting the limitations of non-binding legal structures. Environmental impact assessments and consultation processes exist but often lack enforceability, showing the gap between cooperative norms and legal accountability.

Middle East and North Africa: Scarcity, Security, and Asymmetric Power

The Middle East and North Africa region faces extreme water scarcity compounded by political instability and conflict. Water law here intersects directly with national security and survival concerns. Shared water resources such as the Jordan River, Tigris–Euphrates system, and transboundary aquifers are governed by a mix of bilateral agreements, customary practices, and unilateral measures.

Legal frameworks tend to be weakly institutionalized, with power asymmetries heavily influencing outcomes. International law principles are frequently invoked in diplomatic discourse but rarely adjudicated. Desalination, wastewater reuse, and technological solutions play a disproportionate role, reducing dependence on shared surface water but raising questions about environmental sustainability and equitable access.

Human rights law has gained increasing relevance in the region, particularly where water scarcity intersects with occupation, displacement, and humanitarian crises. Courts and UN bodies have begun to frame water deprivation as a rights violation, signaling an emerging legal pathway where traditional water law mechanisms have failed.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Basin Organizations and Development-Driven Governance

Sub-Saharan Africa has embraced river basin organizations as a primary governance model. The Nile Basin Initiative, Niger Basin Authority, and Senegal River Basin Development Organization reflect attempts to institutionalize cooperation across multiple states with varying capacities and interests.

Legal frameworks in the region emphasize development, energy generation, and food security, often supported by international financing. While treaties and basin charters incorporate equitable utilization and environmental protection, implementation remains uneven due to limited resources, political instability, and competing national priorities.

Recent developments show increasing attention to climate resilience, community participation, and ecosystem protection. Constitutional recognition of environmental rights in several African states has strengthened domestic enforcement, linking regional water governance to national judicial oversight.

Europe: Integrated, Binding, and Rights-Oriented Regulation

The European Union represents the most legally integrated regional water governance system. The EU Water Framework Directive establishes binding obligations for member states to manage water resources at the river basin level, achieve ecological status targets, and ensure public participation.

European water law explicitly integrates environmental protection, water quality, and quantitative management. Groundwater, surface water, and coastal waters are regulated within a unified framework, supported by enforcement through EU institutions and domestic courts.

Human rights jurisprudence further reinforces water governance. The European Court of Human Rights has held states accountable for regulatory failures leading to environmental harm and loss of life, effectively constitutionalizing water safety obligations.

Latin America: Constitutionalization and Social Equity

Latin American water law is notable for its constitutional innovation. Several countries have recognized water as a fundamental right, reshaping allocation and privatization policies. Courts in the region frequently intervene to protect access to water for marginalized communities, linking water governance to social justice.

Transboundary cooperation exists but is less institutionalized than in Europe or Africa. Domestic constitutional law often provides stronger enforcement mechanisms than international treaties, highlighting the growing role of national courts in advancing global water law principles.

North America: Federalism, Property Rights, and Adaptive Governance

In North America, water governance reflects federal structures and strong property-rights traditions. The United States relies on a complex interaction between federal environmental regulation and state-controlled water allocation systems. While surface water and groundwater are regulated differently across states, federal law plays a dominant role in water quality, wetlands protection, and endangered species conservation.

Litigation is a central enforcement mechanism. Civil liability, regulatory penalties, and judicial review create economic deterrence, complementing administrative oversight. Climate change has prompted increasing experimentation with adaptive management, water markets, and interstate compacts.

Canada emphasizes cooperative federalism and basin-based planning, with strong protections for Indigenous water rights increasingly recognized through constitutional and judicial processes.

Legal Framework for Water Management in the U.S.

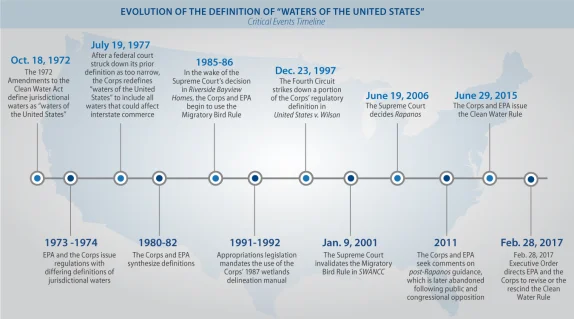

Water law in the United States continues to operate through a complex federal-state framework in which surface water and groundwater are regulated under distinct doctrines shaped by historical practice, regional hydrology, and constitutional principles. In the United States, water law entered a new phase of uncertainty following the Environmental Protection Agency’s late-2025 proposal to significantly narrow the definition of “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS).

Source: EPA – Waters of the United States

Federal Water Laws

Clean Water Act (CWA): Establishes federal authority over “navigable waters” through pollution control requirements, wetland protection under Section 404, and water quality standards. The November 2025 proposed rule would significantly narrow CWA jurisdiction following Supreme Court decisions.

Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA): Protects public health by regulating drinking water quality, establishing maximum contaminant levels, and requiring treatment technologies. EPA sets standards for over 90 contaminants including microorganisms, chemicals, and radionuclides.

Wild and Scenic Rivers Act: Preserves selected rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values in free-flowing condition, prohibiting dams and other development that would harm river values.

Federal Power Act: Authorizes Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to license hydropower projects on navigable waters, requiring consideration of fish and wildlife, recreation, and water quality.

State Water Rights Systems

States retain primary authority over water allocation, employing three principal systems.

Prior Appropriation (Western States): “First in time, first in right” system where water rights depend on beneficial use priority dates. Senior rights holders receive full allocation before junior rights holders during shortages. Rights can be lost through non-use and generally allow transfer to new uses or locations.

Riparian Rights (Eastern States): Landowners adjacent to water bodies have rights to reasonable use that doesn’t unreasonably interfere with other riparians. Rights attach to land ownership and generally cannot be transferred separately from land.

Hybrid Systems: Some states employ combinations incorporating elements of both doctrines.

Interstate Water Allocation

Rivers crossing state boundaries require allocation through:

Federal Project Operations: Bureau of Reclamation manages major water projects

Congressional Compacts: Colorado River Compact allocates flows among seven basin states

Interstate Compacts: Negotiated agreements among states with congressional approval

Supreme Court Decrees: Equitable apportionment when states cannot agree

Comparative Lessons for Global Water Law

Comparative analysis reveals several consistent patterns. First, legal effectiveness depends less on the articulation of principles than on institutional capacity and enforcement mechanisms. Second, rights-based approaches increasingly supplement traditional allocation doctrines, particularly in contexts of scarcity and inequality. Third, climate change demands legal flexibility that older treaty regimes often lack.

Across regions, global water law is converging toward a model that prioritizes sustainability, cooperation, transparency, and human rights. Yet divergence persists in enforcement, reflecting political realities and economic disparities. Bridging this gap remains the central challenge for global water governance in the coming decade.

Future Directions and Policy Challenges

Sustainable water management faces evolving pressures requiring innovative legal and institutional responses.

Emerging Contaminants

PFAS, pharmaceuticals, and microplastics challenge conventional treatment and require:

- Expanded monitoring programs

- Treatment technology development

- Source control strategies

- Revised water quality standards

Water-Energy Nexus

Recognizing water-energy interdependencies:

- Thermoelectric power requires massive water

- Water treatment and distribution consume energy

- Hydropower provides renewable electricity

- Integrated planning optimizing both resources

Indigenous Water Rights

Federal reserved rights for tribes require:

- Quantification through adjudications or settlements

- Infrastructure funding for beneficial use

- Co-management of shared resources

- Cultural and spiritual values recognition

Technological Innovation

Advances enabling improved management:

- Improved weather and climate forecasting

- Real-time monitoring networks

- Advanced metering infrastructure

- Satellite-based water accounting

- Artificial intelligence optimizing operations

Conclusion

By 2026, global water law stands at a critical juncture. The legal principles governing water are well established, but enforcement and coordination remain uneven. Climate change, population growth, and environmental degradation demand a shift from fragmented regulation to integrated, rights-based, and adaptive governance.

Sustainable water management is no longer a technical policy choice but a legal imperative grounded in international law, human rights, and environmental protection. The effectiveness of global water law will determine not only resource sustainability but also social stability, economic resilience, and peace in an increasingly water-scarce world.

Integrated water resources management principles emphasizing basin-scale approaches, stakeholder participation, and surface-groundwater coordination provide pathways toward sustainability. Groundwater and surface water regulations establish allocation systems balancing economic uses with environmental flows while water quality standards protect designated uses.

Environmental compliance requirements under the Endangered Species Act, Clean Water Act, and state laws ensure water development proceeds without causing unacceptable ecosystem harm. Climate change adaptation represents an urgent priority requiring flexible management, enhanced storage, conservation, and institutional innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is global water law?

Global water law consists of international treaties, customary law, human rights obligations, and environmental principles governing water allocation, quality, and ecosystem protection.

Is access to water a human right?

Yes. International human rights law recognizes access to safe drinking water and sanitation as a fundamental right linked to life, health, and dignity.

How are transboundary rivers regulated?

Through principles of equitable and reasonable utilization, no significant harm, cooperation, and prior notification, reflected in treaties and customary law.

How does climate change affect water law?

Climate change requires adaptive management, flexible allocation, drought planning, and integration of climate risk into legal frameworks.

What is the biggest challenge in global water governance?

The primary challenge is translating well-established legal principles into effective, coordinated enforcement across jurisdictions and sectors.

What laws govern sustainable water resource management in the United States?

Key laws include the Clean Water Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, Federal Power Act, Endangered Species Act, NEPA, and state water rights statutes.

How do federal and state water authorities differ?

What is Integrated Water Resources Management?

IWRM is a governance framework coordinating surface water, groundwater, land use, and ecosystems at the watershed level to balance economic, social, and environmental needs.

How is groundwater regulated in 2026?

States rely on permit systems, withdrawal limits, reporting requirements, critical management areas, and conjunctive management to address overdraft and contamination.

What compliance requirements apply to water users?