Explore why the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) still shapes Global Power in 2026, its legal framework, global conflicts, and real-world impact.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) stands as humanity’s most translated document and the foundation of international human rights law. Adopted by the United Nations on December 10, 1948, the UDHR proclaims the inalienable rights to which every human being is entitled, regardless of race, color, religion, sex, language, political opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, or other status.

According to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights:

“The UDHR has been translated into more than 500 languages, making it the most translated document in the world.”

As we commemorate the 76th anniversary in 2025, the UDHR’s 30 articles continue guiding human rights treaties, national constitutions, and international law while inspiring movements for dignity and equality worldwide. This comprehensive guide examines the UDHR’s history, key articles, legal significance, and enduring impact on global human rights protection.

What Is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights represents the first comprehensive statement of human rights principles adopted by the international community.

United Nations explains that:

“The UDHR sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and has become a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations.”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emerged from the aftermath of World War II, when the international community sought to prevent the atrocities that had occurred during the conflict. The UDHR was adopted without dissent but with eight abstentions on December 10, 1948, at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris. The abstaining countries were the Soviet Union, Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and Yugoslavia.

While not a legally binding treaty itself, the UDHR has achieved customary international law status through widespread acceptance and forms the foundation for two binding UN human rights covenants: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Together, these three documents comprise the International Bill of Human Rights.

Historical Context and Drafting Process

The UDHR’s creation involved diverse voices from around the world working to establish universal principles transcending cultural, political, and ideological differences.

Post-War Imperative

The horrors of World War II, including the Holocaust and widespread human rights violations, created urgent consensus that international human rights standards were essential to prevent future atrocities. The UN Charter, adopted in 1945, committed member states to promoting “universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

The Drafting Committee

The UN Commission on Human Rights, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt appointed a drafting committee to create the declaration. Key figures included René Cassin of France, Charles Malik of Lebanon, Peng Chun Chang of China, and John Humphrey of Canada, who prepared the initial draft. This diverse committee ensured the declaration reflected various philosophical and cultural traditions rather than exclusively Western values.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s leadership proved instrumental in navigating political tensions during the Cold War period. She emphasized the declaration’s universality and worked tirelessly to achieve consensus among nations with vastly different political systems and cultural backgrounds. The drafting process involved extensive consultations and revisions over nearly two years before the General Assembly’s final adoption.

Global Consultation

The drafting committee solicited input from governments, non-governmental organizations, and scholars worldwide. This inclusive process helped create a document reflecting diverse perspectives on human dignity, liberty, and justice. Philosophers, religious leaders, and legal experts contributed to articulating principles that would resonate across cultures and civilizations.

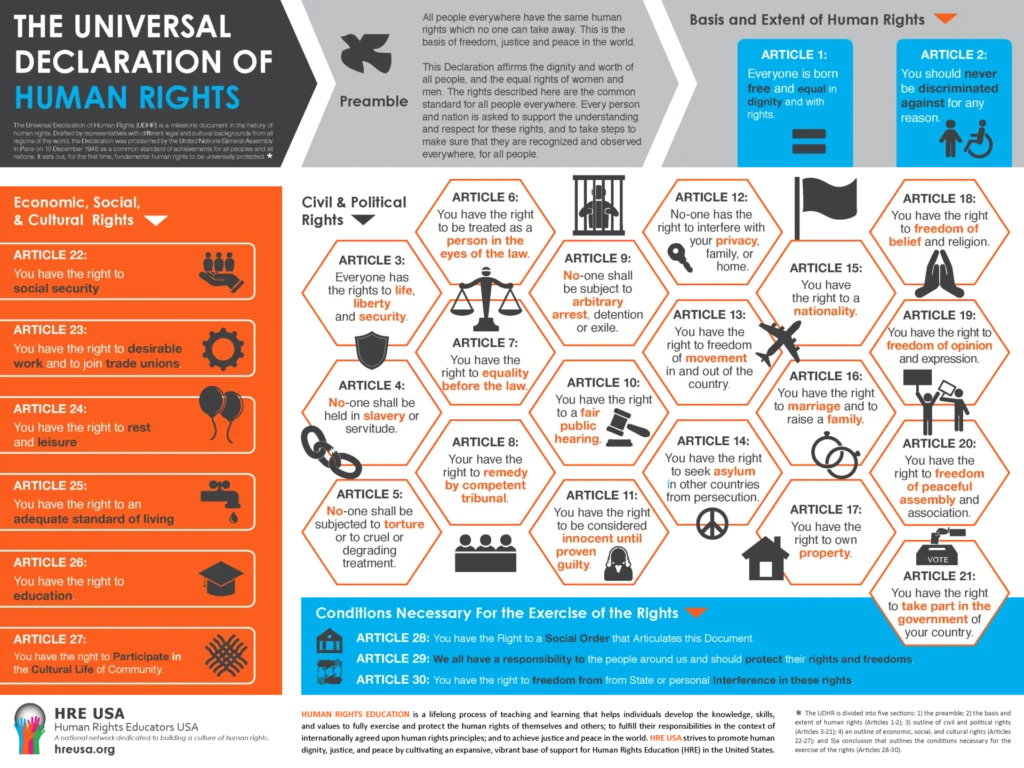

The 30 Articles: Core Rights and Freedoms

The UDHR’s 30 articles establish comprehensive rights covering civil, political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions of human dignity.

Articles 1-2: Foundation Principles

Article 1 proclaims that:

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights, endowed with reason and conscience, and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

This foundational principle establishes human dignity as inherent rather than granted by governments or contingent on characteristics like nationality, wealth, or social status.

Article 2 prohibits discrimination, stating that:

“Everyone is entitled to all rights and freedoms without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

This non-discrimination principle applies universally regardless of the political, jurisdictional, or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs.

Articles 3-21: Civil and Political Rights

These articles protect fundamental freedoms essential for human autonomy and political participation.

Article 3 establishes:

“the right to life, liberty, and security of person, forming the basis for prohibiting slavery, torture, arbitrary arrest, and other violations of personal integrity.”

Articles 4 through 11 prohibit slavery and servitude, torture and cruel treatment, and arbitrary arrest while guaranteeing equality before the law, effective legal remedies, fair trial rights, and presumption of innocence. These provisions establish the rule of law as essential for protecting human dignity against state abuse.

Articles 12 through 17 protect privacy, freedom of movement, asylum from persecution, nationality, marriage and family rights, and property ownership.

Article 13 specifically guarantees:

“the right to leave any country, including one’s own, and to return to one’s country, establishing freedom of movement as a fundamental human right.”

Articles 18 through 21 guarantee freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; freedom of opinion and expression; freedom of peaceful assembly and association; and the right to participate in government through genuine periodic elections with universal and equal suffrage. These political rights enable citizens to shape their governance and hold leaders accountable.

Articles 22-27: Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

The UDHR recognizes that civil and political freedoms cannot be fully realized without economic security and social protection.

Article 22 establishes that:

“Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization of economic, social, and cultural rights indispensable for dignity and free development of personality.”

Article 23 protects:

“the right to work, free choice of employment, just and favorable conditions of work, equal pay for equal work, and the right to form and join trade unions.”

These provisions recognize that economic exploitation undermines human dignity and that workers deserve fair treatment and the ability to organize collectively.

Articles 24 and 25 guarantee rest and leisure, including reasonable working hours and periodic holidays with pay, and an adequate standard of living, including food, clothing, housing, medical care, and necessary social services.

Article 25 specifically provides that:

“Everyone has the right to security in unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age, or other lack of livelihood circumstances beyond their control.”

Article 26 establishes:

“the right to education, specifying that elementary education shall be free and compulsory, technical and professional education generally available, and higher education equally accessible based on merit.”

Education shall be directed to the full development of human personality and strengthening respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms while promoting understanding, tolerance, and friendship among nations, racial, and religious groups.

Article 27 protects:

“the right to participate in cultural life, enjoy the arts, and share in scientific advancement and its benefits, while also protecting moral and material interests resulting from scientific, literary, or artistic production of which a person is the author.”

These cultural rights recognize that human flourishing requires access to knowledge, creativity, and cultural expression.

Articles 28-30: Implementation Framework

Article 28 states that:

“Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms outlined in this Declaration can be fully realized.”

This provision recognizes that effective human rights protection requires both national institutions and international cooperation creating conditions enabling rights enjoyment.

Article 29 acknowledges that:

“Everyone has duties to the community and that rights exercise may be subject only to limitations established by law for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and meeting the just requirements of morality, public order, and general welfare in a democratic society.”

This balancing recognizes that rights exist within social contexts requiring reasonable limitations to protect legitimate societal interests.

Article 30 provides that:

“nothing in the declaration may be interpreted as implying any right to engage in activity or perform acts aimed at destruction of any rights and freedoms set forth therein.”

This safeguard prevents misuse of the declaration to undermine the human rights it seeks to protect.

Legal Status and International Influence

While originally conceived as a non-binding declaration, the UDHR has achieved profound legal and political significance through its influence on international law, national constitutions, and court decisions worldwide.

Customary International Law Status

Legal scholars increasingly recognize that many UDHR provisions have attained customary international law status through consistent state practice accompanied by a sense of legal obligation. Prohibitions on slavery, torture, and genocide, along with principles of non-discrimination and self-determination, are now considered jus cogens norms binding on all states regardless of treaty ratification.

Foundation for Human Rights Treaties

The UDHR inspired numerous international human rights treaties creating legally binding obligations. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, both adopted in 1966, elaborate the UDHR’s principles into comprehensive treaty obligations.

Regional human rights instruments, including the European Convention on Human Rights, American Convention on Human Rights, and African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, draw heavily from UDHR principles while addressing regional contexts.

Specialized treaties addressing particular issues or vulnerable groups, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Convention on the Rights of the Child, Convention Against Torture, and Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, build upon the UDHR’s non-discrimination principle and commitment to human dignity.

Constitutional Incorporation

More than 90 national constitutions incorporate UDHR provisions or explicitly reference the declaration, demonstrating its global influence on domestic legal systems. Constitutional courts worldwide cite the UDHR when interpreting fundamental rights provisions, treating it as authoritative guidance on human rights content and scope.

Some countries grant the UDHR direct legal effect in their domestic legal systems, allowing courts to apply its provisions when adjudicating cases. Even where not directly enforceable, the UDHR serves as an interpretive guide helping courts determine the meaning and scope of constitutional rights protections.

International Monitoring Mechanisms

UN treaty bodies monitoring compliance with human rights conventions regularly reference UDHR principles when evaluating state reports and issuing recommendations. The UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review process assesses all UN member states’ human rights records using UDHR standards as benchmarks for evaluation.

UDHR and Human Rights Education

Promoting understanding of human rights through education represents a critical component of the UDHR’s ongoing implementation and relevance.

Human Rights Day

December 10 marks Human Rights Day, commemorating the UDHR’s adoption and providing an annual opportunity to reflect on progress and remaining challenges. The UN and human rights organizations worldwide use this day to raise awareness, highlight violations, and advocate for strengthened protections.

Educational campaigns during Human Rights Day reach millions with messages about fundamental rights and individual responsibility to respect others’ dignity.

Educational Mandates

Article 26 specifically requires that education be directed toward strengthening respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. Schools worldwide incorporate human rights education into curricula, teaching students about their rights and responsibilities in democratic societies. Universities offer specialized human rights programs training the next generation of advocates, lawyers, and policymakers working to advance UDHR principles.

Public Awareness Campaigns

The wide availability of the UDHR in over 500 languages facilitates grassroots human rights education globally. Organizations translate the declaration into local languages and dialects, making its principles accessible to communities that might otherwise remain unaware of their rights. Simple language versions help children and adults with limited literacy understand fundamental human rights concepts.

Role of Civil Society

Non-governmental organizations play essential roles in monitoring compliance, documenting violations, providing legal assistance, and advocating for policy changes consistent with UDHR standards. Groups like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and countless local organizations draw on UDHR authority when challenging abuses and demanding accountability from governments and other powerful actors.

Global Impact of the UDHR in 2026

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) remains the cornerstone of international human rights protection in 2026, shaping how the world understands justice, dignity, and state responsibility during conflict and political crisis. Although the declaration itself is not legally binding, it continues to function as the global benchmark for lawful conduct, influencing international courts, binding treaties, humanitarian law, and accountability mechanisms.

In an era marked by the Israel–Gaza conflict, the Russia–Ukraine war, political instability in Venezuela, and rising geopolitical tensions worldwide, the UDHR’s relevance has only intensified.

From a search and discovery perspective, the UDHR is now widely referenced not only in academic and legal contexts but also in real-time policy debates, international litigation, and humanitarian reporting. Its principles help answer a question millions are searching for in 2026:

“What rules still apply when the world is in crisis?“

How UDHR Functions as Law in 2026

In practical terms, the UDHR operates as the foundation upon which binding international legal systems are built. Nearly all of its principles have been codified into enforceable treaties, such as international covenants on civil, political, economic, and social rights, and are reinforced by international humanitarian law during armed conflict.

Courts and legal bodies consistently use the UDHR as an interpretive guide when determining whether states have met their obligations related to the right to life, freedom from torture, equality before the law, and access to justice.

In 2026, the declaration also plays a critical role in international accountability. Allegations of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and large-scale human rights violations are assessed using legal standards that trace directly back to UDHR principles. This makes the declaration a living framework rather than a historical document, influencing judgments, sanctions regimes, and diplomatic pressure across regions.

Israel–Gaza in 2026: Civilian Protection and Human Rights Obligations

The crisis involving Israel and Gaza demonstrates how the UDHR continues to shape international legal and humanitarian discourse. In 2026, global attention remains focused on civilian casualties, access to humanitarian aid, protection of medical facilities, and the basic rights to food, water, shelter, and healthcare. These concerns directly reflect UDHR guarantees related to human dignity and the right to life.

Legal discussions increasingly emphasize that even during armed conflict, states remain bound by obligations to protect civilians and avoid disproportionate harm. The UDHR informs how international courts, UN bodies, and humanitarian organizations evaluate compliance, responsibility, and prevention of further violations. As a result, the declaration is not only cited in moral arguments but also embedded in legal proceedings and international rulings.

Russia–Ukraine War: War Crimes, Accountability, and Human Rights Law

The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine remains one of the clearest modern examples of UDHR principles in action. In 2026, international concern continues over attacks on civilian infrastructure, forced displacement, treatment of prisoners of war, and the long-term humanitarian impact on millions of civilians.

These issues are assessed through international humanitarian law and international criminal law, both of which draw their ethical and legal foundations from the UDHR. Investigations into alleged war crimes reinforce the declaration’s enduring message: serious human rights violations do not lose their legal significance due to political complexity or ongoing negotiations. Accountability remains a core expectation of the international system.

United States and Venezuela: Due Process, Political Rights, and International Law

Tensions involving the United States and Venezuela highlight another dimension of UDHR relevance in 2026. Here, the focus shifts toward due process, fair trial standards, political participation, and the humanitarian consequences of sanctions and international pressure.

The UDHR provides the framework used by international observers to evaluate whether actions respect sovereignty while still protecting fundamental rights. Discussions surrounding civilian protection, legal detention, and political freedoms consistently reference UDHR principles, showing how the declaration applies not only in war zones but also in complex political and diplomatic confrontations.

Global Human Rights Trends Reflecting the UDHR in 2026

Beyond headline conflicts, the UDHR continues to shape responses to global challenges such as mass displacement, refugee protection, digital surveillance, censorship, suppression of protests, and restricted humanitarian access.

In many regions, governments face increasing scrutiny over arbitrary detention, erosion of judicial independence, and limitations on freedom of expression. Despite cultural and political differences, the UDHR remains the universal standard used to assess whether state actions align with internationally accepted human rights norms.

Why the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Still Matters in 2026

The UDHR remains vital in 2026 because it provides a shared global definition of human dignity that transcends borders and political systems. It supplies the language used by courts, governments, journalists, and civil society to identify injustice and demand accountability. While the declaration does not enforce itself, it shapes the laws, institutions, and mechanisms that do.

In a world increasingly defined by conflict, polarization, and humanitarian emergencies, the UDHR continues to guide legal interpretation, influence international rulings, and remind the global community that human rights are universal and non-negotiable—even in times of crisis.

Conclusion

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights stands as humanity’s most comprehensive statement of fundamental rights and freedoms essential for human dignity. Its 30 articles establish civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights that states must respect and protect. While not originally intended as a legally binding treaty, the UDHR has achieved immense legal and moral authority influencing international law, national constitutions, and social movements worldwide.

The declaration’s enduring relevance in 2025 reflects both the universality of its principles and the persistence of human rights challenges requiring continued advocacy and action. From protecting digital privacy to addressing climate change, from defending democratic freedoms to advancing economic equality, UDHR principles guide efforts to create more just and humane societies. Universal Declaration truly belongs to all humanity and speaks to the deepest yearnings for dignity, justice, and peace that unite us across all differences.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights remains the ethical and legal backbone of the international system in 2026. Its authority comes not from enforcement power but from universal acceptance, consistent legal integration, and continued relevance in the world’s most urgent crises. As global challenges evolve, the UDHR continues to define what humanity owes to every individual and how the world measures justice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights legally binding?

No. The UDHR itself is not legally binding, but many of its principles are part of customary international law and legally binding treaties like the ICCPR and ICESCR.

Why is the UDHR important today?

The UDHR sets global human rights standards. It guides laws, court decisions, education systems, and international accountability even in modern issues like digital rights.

How many rights are in the UDHR?

The UDHR contains 30 articles, covering civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights necessary for human dignity and freedom.

Who wrote the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

The UDHR was drafted by the UN Commission on Human Rights, led by Eleanor Roosevelt, with contributions from global leaders and legal scholars.

How does the UDHR affect everyday life?

The UDHR influences national laws, protects freedom of speech, equality, education, work rights, and provides a global benchmark for justice and human dignity.

Does the UDHR apply during war?

Yes. Human rights continue to apply during armed conflict alongside international humanitarian law, reinforcing civilian protection and accountability.

How does the UDHR affect global conflicts today?

It shapes legal interpretations, war crimes investigations, humanitarian obligations, and international pressure on states involved in conflicts.